Long Shots—Too Far to Really Tell

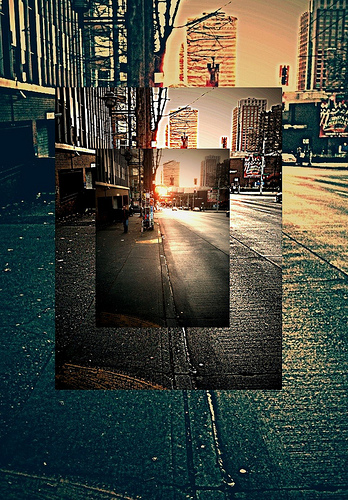

We’ve been looking at the three basic stationary distance shots and have covered Close-Ups (Close Shots) and Full Shots (Medium Shots). Now we’re going to consider Long Shots, which have very specific and useful purposes in both films and novels.

Long Shots in novels are not often used. Why? Well, when you are a half mile away from something, you really can’t see all that much. But that is exactly why and when you want to use this particular shot. We looked at the use of Long Shots for Establishing Shots, but they can be used in other ways.

Anytime you want to create a mystery or show something fuzzy, not clearly seen or defined, a Long Shot can be the right choice of camera angle. Something observed can be mistaken or misinterpreted, a voice yelled can go unheard, a danger coming up over the horizon can be unnamable and thus more terrifying. A tornado or hurricane roiling in the distance can build tension. Knowing what may be coming or what may be happening can add great microtension to a novel. So you might do well to look for opportunities in your story to use a Long Shot.

Long Shots Are Great for Showing the Big Picture

Then there are the epic or panorama views you want the reader to see and feel. Whether showing a glorious morning bursting upon the beach after a terrific storm or a scene like the one in Gone with the Wind, in which the whole of Atlanta is burning and Rhett and Scarlett are fleeing in the wagon, nothing beats a Long Shot for effect (well, actually that was a studio lot in Culver City, and it was agreed they’d shoot this scene first to get rid of some old sets to make way to build the new ones needed of the plantations and city streets for the rest of the movie—just to throw in a bit of movie trivia here).

Action-packed movies are a blend of Close-ups and Long Shots (and just about every moving shot too). The camera narrows in on the faces of the actors as they tensely rig the bomb to blow, then cuts to the Extreme Long Shot to show the massive explosion. Disaster movies have Long Shots galore, and if you are writing an action-suspense novel you’ll want a lot of Long Shots in your scenes—shown from the POV characters’ eyes. Find ways to position your characters so they can see the “big picture” of what is happening around them.

Long Shots Can Delay Resolution and Add Tension

Take a look at the ending of suspense writer Terry Blackstock’s first scene in her novel Predator. The short chapter opens in the mire of tragedy. Krista is at hope’s end. Her younger teenage sister, Ella, has been missing for two weeks now, and the news she has dreaded hearing comes to her: the police have found the body of a girl in the woods. They take Krista to the crime scene to see if she can identify the brutally murdered and partially buried body—a powerful, riveting opening to the book. But watch how Blackstock uses the camera effectively to build tension. She doesn’t just take her protagonist straight to the body, close up and personal. Instead, she draws out the moment with a Long Shot.

He [the officer] took her arm and walked her toward the investigators. When she reached them, she realized the body was another twenty-five yards beyond them. “You can’t go any closer,” the lieutenant said in a soft voice, “There could be footprints or trace evidence.” . . .

Nausea rose, but she stood paralyzed, staring toward the mound of dirt where the girl lay. She couldn’t see a thing. Not what she was wearing or the color of her hair . . .

Krista waited, willing back the numbness, certain she wouldn’t recognize the girl. As the first raindrops fell, a man in a medical examiner’s jacket took in a gurney, and Krista watched as they pulled the body from its shallow tomb. She saw the pink-striped shirt that Ella was wearing that last day. Blonde hair matted with blood and earth.

Her knees went weak, turned to rubber. She dropped and hit the ground. At once, a crowd of police surrounded her, asking if she was okay. She blinked and sat up, let them pull her back to her feet.

Ella!

She heard footsteps pounding the dirt.

“Aw, no! No! It can’t be her!” Her father’s voice, raspy and heart-wrenching, wailed out over the crowd. She wanted to go to him, comfort him, but it was as though her hands were bound to her sides and her legs wouldn’t move.

As they brought the girl closer, Krista saw the bloody, bruised face. Ella’s face.

The search was over. Her sister was dead.

By Blackstock having her character first unable to see a thing, only a mound of dirt, she stretches out the tension for the reader. Krista has to wait (and so does the reader) agonizing moments until the body is pulled out and she can make out the shirt and the hair—not the face, because she’s not close enough—but seeing the shirt is conclusive enough for her. That bit of delay in identifying the body as Krista’s sister was deliberate, and Blackstock chose the Long Shot for that reason.

Use a Long Shot to Show Surroundings

Here’s another wonderful example of a Long Shot—a great choice by author Philippa Gregory in her best seller The Other Boleyn Girl. Notice the details her character, young Mary, can see from where she stands—and what she can’t see. It’s the perfect opening shot to give a sense of the scope of the crowd and the event taking place, but close enough for Mary to note the subtle actions and expressions of those she is watching.

I could hear a roll of muffled drums. But I could see nothing but the lacing on the bodice of the lady standing in front of me, blocking my view of the scaffold. I had been at this court for more than a year and attended hundreds of festivities, but never before one like this.

By stepping to one side a little and craning my neck, I could see the condemned man, accompanied by his priest, walk slowly from the Tower toward the green where the wooden platform was waiting, the block of wood placed center stage, the executioner dressed all ready for work in his shirtsleeves with a black hood over his head. It looked more like a masque than a real event, and I watched it as if it were a court entertainment. The king, seated on his throne, looked distracted, as if he was running through his speech of forgiveness in his head. Behind him stood my husband of one year, William Carey, my brother, George, and my father, Sir Thonas Boleyn, all looking grave. I wriggled my toes inside my silk slippers and wished the king would hurry up and grant clemency so that we could all go to breakfast. I was only thirteen years old, I was always hungry.

The Duke of Buckinghamshire, far away on the scaffold, put off his thick coat. He was close enough kin for me to call him uncle. . . .

Uncle Stafford came to the front of the stage to say his final words. I was too far from him to hear, and in any case I was watching the king, waiting for his cue to step forward and offer the royal pardon. The man standing on the scaffold, in the sunlight of the early morning, had been the kind’s partner at tennis, his rival on the jousting field, his friend at a hundred bouts of drinking and gambling, they had been comrades since the king was a boy. The king was teaching him a lesson, a powerful public lesson, and then he would forgive him and we could all go to breakfast.

Mary can tell by the king’s expression that he seems distracted—that’s something she wouldn’t be able to tell from too far away. Yet she is not close enough to hear the words being said by her uncle. No doubt, at an occasion such as this, she would not be able to get too close, and Gregory’s use of the Long Shot invites more emotional punch by Mary not being able to discern clearly that the outcome of this affair will turn out much differently than she expected.

Long Shots Make Great High Moment Shots

Long Shots “blow up” a scene, make it huge and powerful. They can also add subtle poignancy when the hero rides off into the sunset (or whatever that equates to in your book and genre). Long Shots can say “This is the result of what just happened.” That moment often ranks as a high moment in a scene, and even for the entire novel.

Sometimes filmmakers will use an Extreme Long Shot to emphasize the vastness of location, usually following a Close-up, indicating the character has just seen or realized something important, and those two shots in sequence add tension. Novelists can do the same in their scenes.

Do you recall how the movie Casablanca ends? Rick and Louis walk together (Two Shot) and then head off across the Tarmac (Follows), which shifts the scene into a Long Shot. Instead of the camera moving, the actors move farther and farther away. Can you think of a better shot to go with Bogart’s famous line, “Louis, I think this is the beginning of a beautiful friendship”? I can’t. The Long Shot lingers long in the mind—a great tool to put in your cinematic toolbox.

This week, think of a scene or two in your novel in which you can effectively use a Long Shot. Is there something you want your character to see from far away, something that should be left vague? Is there a high moment in which you need to show a broad scope, a bigger picture that will emphasize or reveal something crucial to your story? If not, can you think of a place to put one in?

This series, Shoot Your Novel, has been very useful to me. I am not writing a novel, but short stories and a memoir. But I am an inexperienced writer, so I’m grateful for all the good instruction and ideas that I can find. Thank you.

Thanks, Fran. You can certainly utilize all these cinematic techniques for short stories and narrative nonfiction like memoirs. Glad the posts are helping you!

First off, I love how you equate screenwriting and filmmaking with that of the novel. This type of scene so carefully illustrated by you, Fran, presents a way to involve the reader in both the big picture and in through the mind of the character. It’s a new method of showing not telling for me to use. I love it!