Why Write Fiction? The Page versus the Screen

Today’s guest post is by author and screenwriter William Thacker:

There is more than one way to write a novel, and whenever an author imparts his wisdom on the subject, it should be accompanied by a disclaimer: “In my humble opinion.” A rich and diverse publishing scene doesn’t mean that everyone should write the same way—language is a near-infinite library from which you should be able to pick ’n’ mix however you please.

However, given that the novel is perhaps the default form of choice for aspiring writers—as opposed to writing plays or the ingredients on a cereal box—it’s never a wasted exercise to reflect on what makes a novel a novel in the first place. In doing so, we can all become the best version of ourselves and live happily ever after.

Hearing or Seeing Your Story

It’s not unreasonable to suggest that many writers don’t choose to write prose fiction but rather the form chooses them. Perhaps Dickens would have been a playwright had he lived in Elizabethan England at the time of Shakespeare. Had they been writing in the television age, the great wave of mid-twentieth-century American playwrights (Miller, Williams, O’Neill, Albee) may have been entranced by the screen rather than Broadway. In Shakespeare’s time, theatre as a mass medium owed much to mass illiteracy. Maybe the Bard of 2014 would have been on Twitter.

The novel—which I’m crudely using as shorthand for prose fiction—is the de facto literary form in contemporary culture; as such, you could forgive many emerging writers for wanting to cram their best ideas into novel form. But all things being equal, what is the essence behind prose fiction as opposed to screenplay writing? It’s something I’ve thought about (for a second or two) in my humble experience as a first-time novelist and screenwriter.

One possibility is that playwrights and screenwriters hear language whereas novelists see it—and indeed feel it, immerse themselves within it, and take it out for dinner. The text-based nature of prose fiction—compared to the audio-visual screen or theatre—compels the author to forge a one-on-one connection with the reader through the sole means of language alone. In this respect, the greatest weapon a novelist possesses is her voice—not her own voice but a cultivated narrative voice that is just as unique as when you talk aloud. Find your voice, as the cliche goes.

The Burden of the Writer

The creative process for any artist is arguably about how you manipulate your materials to make the guitar, camera, or paintbrush do what you want it to do. For a novelist, the only material he has is language—a very base material—so the addiction comes from manipulating language and marveling (or despairing) at the results. Don DeLillo put it well when he told The Paris Review about the addictive challenge in wanting to “exercise your will, bend the language your way, bend the world your way.” The onus on the novelist is to present everything one can’t possibly see or feel on a stage or screen. This is a challenge, of course, but an exciting one.

Screenwriting is a collective act made easier by the talents of many other people—the director, actors, cinematographer, sound recordists, makeup artists, costume assistants, etcetera. If novelists are solitary animals, screenwriters are a herd of elephants complaining about the standard of catering in the unit base.

Screenwriting is a collective act made easier by the talents of many other people—the director, actors, cinematographer, sound recordists, makeup artists, costume assistants, etcetera. If novelists are solitary animals, screenwriters are a herd of elephants complaining about the standard of catering in the unit base.

The preparation is done in the buildup—months of round-table chat, script editing, coffee, and rehearsals. Even if you’ve written the perfect shooting script, a scene might be shot seven or eight times, allowing for improvisation or playing a line a different way. The lines are almost a prompt, which intelligent actors can interpret as they see fit. Your job as a screenwriter isn’t to dictate everything; it’s more like carrying a baton to the next relay runner.

What’s certainly true is that the fundamentals of good storytelling are universal. You can possess the most expensive camera equipment and editing suite, but the part that doesn’t cost anything—getting to know your characters—is perhaps the easiest to neglect. The role of a editor when working on a novel is essential for similar reasons; as an author, it’s important to leave your ego at the door and embrace fresh ideas. Whilst there are some cast-iron distinctions between prose fiction and screenwriting, there’s no formula for a good storytelling instinct and hard work.

What are your thoughts? Do you “hear” or “see” your story? Why did you chose the medium you did to write in? What draws you to writing a novel or short story instead of a screenplay (or the reverse)? Have you ever tried to write in a different medium, and if so, what did you experience?

Feature Photo Credit: The Hamster Factor via Compfight cc

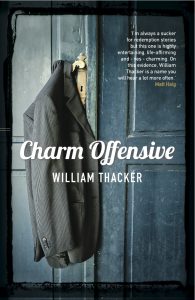

William Thacker is the author of Charm Offensive, just published this March by Legend Press.

William Thacker is the author of Charm Offensive, just published this March by Legend Press.

Great & thought provoking post. Thanks! For me, it’s always been about words. I purely love the sound and feel and look of them. When I’m reading, I find myself ensnared by certain perfect sentences or phrases that demand I read them over and over before I can continue with the story. They’re like fine wine, or that first bite of expensive chocolate–glorious on the tongue. If I can create one line in a story that resonates with any reader in that way, I’m happy.

I’m looking forward to reading Charm Offensive. Thanks again.

Thanks Marcia.

Yes, I like the idea of words being an indulgence, like wine or chocolate as you say! I always liked Oscar’s Wilde’s Picture of Dorian Gray for being unapologetically playful with language. As with many things, I suppose there’s a balance to be struck between romance and pragmatism (love of language versus effective storytelling) but perhaps the two needn’t be mutually exclusive.

All the best,

William

I love writing short stories than novels. I love to pack a punch using just a few words. I think many people in the Internet-era don’t have the time to read full-length novels. Unless the novel is exceptional or stands-out in some way.

Someday I would like to write the script for short Youtube movies. Short stories and Youtube movies are very challenging because there is only as much time a reader/viewer gives you. Often, that’s only a few seconds. If they are not hooked by that time, the ‘x’ button on the top right corner comes in very handy! 🙂

I believe that I tend to ‘see’ my story as I write it. This has been a more recent development in my writing.

By spending more time improving the body language of my characters, I have started physically acting out actions such as hand gestures, to get a better visual on the movement of my protagonist.

Your piece is provocative–and my answer would be I see my story. I see the characters and the setting and when I rewrite I look for more jewel-like words to present everything to the reader. I love stringing words together and find rewriting exciting. Once I know the story, once I know who my characters are and where they are headed, then words even more become my building blocks.

Writing a play or screenplay fascinates me, because so much of the text has to be stripped away and presented in dialogue or setting. Maybe I’ll try that someday. Thanks for your post.

I don’t write fiction at this point; I discovered I was a whole lot better and more interested in nonfiction. But I’ll throw this out, as a writer/reader. I very rarely watch TV or movies. I’d rather be reading. I see the story as I read it, on my own little private cinema screen. No one does better casting than I do and there are no annoying people talking in the theater. My best friend once said that the movies I do like are novels. I countered that that is because the novels I love are movies in my head.