Juries: How They Work, How They’re Chosen, and What Lawyers Handle Them Best

Today’s guest post is by Karen A. Wyle:

Want to write legal thrillers? Or put a courtroom scene in your novel? Movies portray juries listening to evidence and lawyers’ arguments, but there is much to understanding the roles and responsibilities of a juror.

In true lawyer fashion, I’ll begin with a caveat: my experience comes from practicing law in the United States, almost entirely in California and Indiana. While I have my educated guesses about what doctrines exist beyond those borders, you should treat them as guesses rather than gospel.

Understanding the Function of Juries

There’s one very important open secret about how juries function: they can do pretty much whatever they believe to be right and just, even if their verdict conflicts with the applicable law. Rather than some kind of quirk or flaw in the system, this power is a large part of why we have juries at all.

Juries act as a failsafe against laws that the ordinary citizen views as unduly harsh or out of step with current societal values. When the jury comes up against such a law, they may simply refuse to apply it, ignoring whatever detailed instructions the judge may have given to the contrary.

Such a refusal is called “jury nullification.” In the United States, the power to override legal rules can be extrapolated from several US constitutional provisions, and is more explicitly found in a few state constitutions as well. But I would hazard the guess that juries retain this same power in most or all of the legal systems derived from that of Great Britain.

Jurors Can Ignore the Law?

Judges, understandably, would just as soon that jurors didn’t know they have this option. The defense generally won’t be allowed to argue that the jury should ignore the law. The most the defense may be able to do is get a jury instruction citing the “judge of the law and the facts” language if it exists in that state, and then largely contradict it by saying that the jury should follow the law as the judge has explained it to them.

However, many defense strategies are aimed at inciting the jury to ignore the law. Emphasis on the terrible character or misdeeds of a murder victim, for example, may be stressed as much as the court will allow (a tricky endeavor), even when the details don’t support any theory such as self-defense.

Juror Selection

When lawyers don’t want a potential juror to end up on the jury, they may “challenge” that juror. There are two types of challenges: “for cause” and “peremptory.” At least, that’s the case in the United States. Great Britain dropped the use of peremptory challenges some years back.

A challenge for cause should be used when that juror can’t competently and fairly serve as a juror or on that particular jury. Maybe the juror is friends with—or an enemy of—the defendant, or one of the lawyers, or an important witness. Maybe the juror or a member of the juror’s family was the object of a similar civil suit, and is thus likely to favor the defendant, or the victim of a similar crime, and thus likely to favor the prosecution. Maybe the juror has narcolepsy and could fall asleep without warning.

In cases where the death penalty may be imposed (in the US, which has not, unlike the UK, abandoned that penalty altogether), the state may challenge jurors who say they could never vote for that penalty, or that they could not be impartial in a case where the death penalty (so to speak) hangs over the defendant. Critics of this process contend that “death qualified” jurors (as those who pass these tests are called) tend to be more inclined to favor the prosecution at the guilt-versus-innocence phase of the trial.

Lawyers use peremptory challenges to try to craft a jury favorable to their client’s case, based on the lawyer’s experience and/or prejudices. For example, the lawyer for a young man accused of a nonviolent offense may try to stack the jury with motherly types, while the legal team representing a corporate defendant in a product liability lawsuit may look for middle-aged business owners.

A lawyer could theoretically waste peremptory challenges (always limited in number) by trying to fill the jury with blondes, or getting rid of anyone who looks like the lawyer’s brother-in-law. But if the peremptory challenges will have the result of eliminating all jurors of a certain race or gender, the lawyer will have to prove that that isn’t her goal, and that there’s some other, “neutral” explanation for the challenge in question.

Take a Note

It used to be generally prohibited (at least in the US) for jurors to take notes during the trial, perhaps on the theory that they would miss some evidence while writing other evidence down, or that their notes might overemphasize some points. The reality that jurors won’t remember all the evidence without taking notes has led to changes in this rule, at least in some courts. The rules about notes may vary from one jurisdiction or courtroom to the next. A judge in Indiana recently sentenced a juror to thirty days in jail for contempt of court because he took notes on his cell phone.

In many courts, jurors are allowed to ask questions (most often by giving them in writing to the bailiff, who will submit them to the judge for review and possible use). I heartily approve of this trend. I managed to make it onto a jury once and experienced firsthand the frustration of having a pertinent question the lawyers didn’t address. (Was the missing robber in a two-person unarmed robbery as big as the supposed victim or a scrawny little guy like the defendant?)

Consider Your Lawyer Character for Your Story

Finally, what sort of people make the best trial lawyers? Many clients like the idea of a “pit bull” type—an aggressive fighter who’ll demolish the opposition. But this approach is likely to be counterproductive in a jury trial. Jurors tend to side with the underdog and resent any bullying tactics. Nor are they generally fond of sarcasm aimed at opposing counsel or (especially) at witnesses.

Coming on too strong in court can also lead to a reprimand from the judge, which can seriously undermine the lawyer’s credibility. The client is usually better off with one of the many lawyers who speak softly and carry a sense of proportion and people skills. Whatever his or her personal style, however, a really good trial lawyer often has as strong a personal presence, and as much charisma, as any star of stage or screen.

Karen A. Wyle is an award-winning appellate attorney with more than thirty years’ experience. A cum laude graduate of Harvard Law School, she worked for law firms and the California Court of Appeal before establishing her solo practice in Bloomington, Indiana. She has also written and published five novels. Her most recent project is the reference work Closest to the Fire: A Writer’s Guide to Law and Lawyers. Learn more about Karen and her books at her website. Connect with her on Facebook and Twitter.

Karen A. Wyle is an award-winning appellate attorney with more than thirty years’ experience. A cum laude graduate of Harvard Law School, she worked for law firms and the California Court of Appeal before establishing her solo practice in Bloomington, Indiana. She has also written and published five novels. Her most recent project is the reference work Closest to the Fire: A Writer’s Guide to Law and Lawyers. Learn more about Karen and her books at her website. Connect with her on Facebook and Twitter.

Hi Susanne & Karen,

This is an excellent piece! It gives writers a true inside view of a jury’s function and how the theatrics of court “performers” plays out.

In my time as a police officer testifying before juries, then as a coroner directing juries, it never ceased to amaze me just how attentive jurors are. These folks get their lives disrupted, sometimes for weeks on end without reward. And some cases are so horrific that some jurors must be emotionally affected for life.

Something that puzzles me is the American system where jurors are allowed to speak to the media about their deliberations following judgement. In the Commonwealth system, it’s a sacred rule that what’s said in the jury room is never repeated outside to even a friend in privacy, never mind in front of TV cameras where it gets archived to the realm of YouTube.

It strikes me as dangerous practice to allow jurors to be interviewed given that every case has appellate and retrial potential. I wonder if you’d mind commenting to that, Karen.

Good question, Garry. I’d like to know the answer too.

Suzanne, as always, you find the best guests.

Karen, thank you for this valuable information.

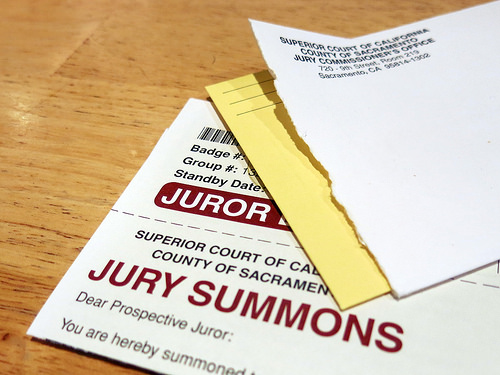

Good piece. I was called for jury duty and for the past three weeks have been worrying about it. I can hardly stand the thought of being on a horrific case, as Garry stated above. Last night I called the number as instructed, and of course, they’ve settled so I didn’t have to appear. Even though I dreaded it, I was disappointed. 🙂 Thanks for the details. Good for everyone to know–not only writers.

Thanks for the informative article. I have served on several juries, one where I was the foreman. I love the experience, but not the delays and short days, and often seeming disregard for the people called to serve. Your article helps me understand some of the details of juries and the law. I want to write about juries someday and your book will be a resource. Thank you.

I’m not a great fan of procedural novels. I am, as an ex-pat, fanatically pedantic about my national identity so I thought I would like to share (courtesy of info please.com) a helpful way to remember the difference between Great Britain and the UK:

“The United Kingdom is a country that includes England, Scotland, Wales, and Northern Ireland. Its official name is “United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland.” England, Wales, Scotland, and Northern Ireland are often mistaken as names of countries, but they are only a part of the United Kingdom.”

So, just to muddy the waters, I’m an ex-pat Brit.

A fascinating glimpse into the juror system. Thank you for sharing!