Scene Structure: The First 3 Things You Need in Your Scene

For this week’s Throwback Thursday, we’re looking at excerpts from past posts on Live Write Thrive that tie in with our exploration on scene structure.

From 3 Things You Must Have in Your Novel’s First Paragraph:

The First Paragraph

That first paragraph is probably going to be the hardest one to write and polish since it carries the biggest burden in your novel (and the last paragraph in the book carries the second biggest burden). It’s fine to just throw something out there to get started, knowing you’ll come back and make it much better.

But before you can write that first paragraph, you should know what your first scene is going to be about—and it has to be about some specific things:

- Your protagonist. Unless you are writing a prologue (if you really must) that involves some other characters, you want that first scene to showcase your protagonist. Why? Because you are clueing your reader and telling her to pay attention to this particular character right from the start. Your reader will assume the first character they are introduced to, with the scene being told in their POV (point of view), is your protagonist and the one they will want to root for. There are exceptions to this, of course, but as a general rule, this is the time-tested and best way to start.

- A catalyst or incident. Your opening scene should start off with a bang, with your protagonist in the middle of something that we sense has been going on for a while. Insinuate a conflict, a problem, some tense situation that puts the protagonist right in the heart of a scene that will be the perfect milieu to showcase her humanity, needs, fears, dreams, or whatever it is you want to reveal about her to the reader at the start. This incident or situation should provide a great platform for your MDQ and plot goal (if you don’t know what I’m talking about, go read the previous posts that go into detail on this). This is why you need to spend some serious time thinking about the setting, locale, and situation of your first scene.

- A hint of the protagonist’s core need. I’ll talk about this more in future posts, but this is essential. Basically, you want to introduce a character who has a visible goal (as we’ve gone over)—but what does that translate to? That she has a need. Hence, the reason she has a goal. If Indiana Jones’s goal is to get the Ark of the Covenant, it’s because he has a need. Now, in a different story, his need may be to get enough money to pay the rent and what is motivating him is his desire not to be homeless, so he’s driven by a need to survive by going after a reward. Or his need could be for fame, for humanitarian purposes, to impress a girl—the list is endless. It’s your story, so you should know why your protagonist wants to reach that visible goal. So hint at what that is.

Now, I’m not suggesting you need to write a three-page first paragraph to get all this in there. In fact, that first paragraph may tell us very little and just give us a great hook and introduce your character in some compelling situation (at very least you need that). But you do need all this on your first page—at least a hint of this. It’s doable—really! And essential to the heart of your story.

From The Defining of a Scene:

How Would You Define a Scene?

If someone asked you to define what a scene is, what would you say? If you think about it, it’s not easy to define. We tend to know when a scene works and when it doesn’t. Here are some elements that make up a scene that I’ve found in books on scene writing:

- The sum of myriad elements that work together [hmm, that’s a bit vague]

- It starts and ends with a character arriving and leaving [sometimes, but not often]

- It can be a single location with many people coming and going

- It gives the sensation that a character is “trapped” in this moment and must go through it

I’m not all that ecstatic about these points. They don’t really tell what a scene is. I mentioned in an earlier post that I like how Jordan Rosenfeld defines a scene in her book Make a Scene: “Scenes are capsules in which compelling characters undertake significant actions in a vivid and memorable way that allows the events to feel as though they are happening in real time.”

What Is Real Time?

Well, it’s not backstory. Too many manuscripts start off with either pages of narrative to set up the book or start with maybe a catchy (or not) first paragraph or two that puts the protagonist right in a scene in real time—meaning they are experiencing something that, for them, is happening right then. Not a memory, not a flashback, not even them thinking about what is happening to them right now.

But after these short moments of establishing the character in a “happening” scene, the author lapses into telling the reader important things they should know [read: back story]. Even if you are going to go heavily into your character’s head, you need that character to be doing it “here and now” in some sort of “capsule” that is unfolding in the moment. It’s not all that complicated, but writers really need to resist the urge to stop the moment or veer off elsewhere.

Be Here Now

So, if you’ve pulled on your reins and disciplined yourself to construct that opening scene with your protagonist in a moment in real time, you now have the structure to show that character undertaking significant actions in a vivid and memorable way. By now you have your themes and MDQs all worked out, and you’ve figured out how to hint at these, along with showing your character’s glimpse of greatness and core need. You’ve set up their persona that they show to the world, and you’ve hinted at their true essence underneath.

Are you starting to feel a bit overwhelmed? You just might be. Not a whole lot of authors can whip up a first scene intuitively and off the cuff that contains every little element needed. And that’s why first page checklist is really helpful. Once you rough in that first scene, go through and make sure you’ve got all the bases covered. Which begs the question . . .

Just How Long Should a Scene Be?

I’ve actually read articles and book chapters that suggest certain numbers of pages, and it’s not that formulaic. Genre can be a factor, since a fast-action thriller may have short, terse chapters whereas a thoughtful literary work may have long ones. The real answer, which may not be so helpful, is that a scene should be as long as it needs to be (the same is true for a novel’s length). You determine the length of the scene by writing it and making sure it reaches its objective. And once it’s done that, it should end.

If you’re interested in more about scene structure, be sure to subscribe to Live Write Thrive so you don’t miss the posts. Mondays we’re going deep into scene structure, and Wednesdays we’re looking at first pages of great novels to see why they work. Join us!

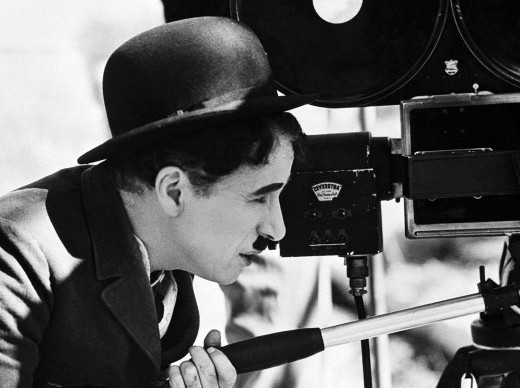

Feature Photo Credit: Julia Manzerova via Compfight cc

I truly enjoy your posts. I learn much from each entry. Just thought I’d share that.

Write On!

Thank you! I hope you get a lot out of this series on scene structure.

Lots of good advice here!!

I really like this idea of going back to past posts. For starters, why reinvent the wheel and secondly, going over past material is needed to cement in all we need to know. I am currently working through your Writing the heart of your Story, as I revise my second novel and it does deal with the setup of the novel and those opening scences. Thanks once again for all your hard work.

Thank you! Glad the posts and books are helping you with your novel!

I’ve considered all the things you mentioned and the key one about backstory is the reason why I’ve decided to scrap the first two pages which were all scene setting and not vital to the novel at all. I like the looks of things better now but maybe I will think a bit more on it later…

Several books in now, I find this advice very relevant other than that things always must step off with the protagonist. When you write in series, your protagonist is typically the main character throughout the series but the event that draw him or her into each new story very widely as do the ways the stories begin. Being formulaic with how the story sets up seldom keeps readers coming back.

To use an example, my newest novel (soon to be released) starts off with one character ordering two others to do something that sets off a long chain of events involving a half dozen other secondary but prominent characters. My protagonist – the sheriff and driver of the story that has to figure out what in the world is going on – doesn’t even appear in chapter one in this book. Series followers know the Sheriff will be involved but they get to the mystery up front this time and the get to wring their hands at everything that happens until she figures it all out.