How to Layer Scenes in a Romance Novel

This week (and for over some additional weeks) I’m going to show you how you can layer those next ten scenes in a romance novel. Maybe you don’t write romance, but don’t navigate away. There are some key elements to structuring romance novels that you may want to incorporate in your fantasy novel or thriller.

Many popular movies of various genres have that “romance” engine as a subplot (see last week’s post on how to layer in subplots). Ones that come to mind are Outbreak, Armageddon, Speed, Star Wars, and on the list goes.

In other words, don’t pooh-pooh romance. Real life includes romance, and many novels can benefit by a romance component. And hey, more than 50 percent of all ebook sales are romance novels. Just sayin’ . . .

What’s Different about the Romance Journey

We looked at one method last week that showed you how you can build on your ten foundational scenes by layering with your key subplot. And you can use that method with a romance novel or any other genre, I believe.

But there are some important things to understand about romance novels—the primary thing being the romance story engine.

Think of it this way: most novels have one engine that drives the story (think of a train or car). There is one primary focus or plot the protagonist is involved with.

But with a romance thread, you have two engines. You still have the overarching plot or story line. But you also have a romance engine, and while romance, like any other genre, can vary in large degrees, the primary “lover’s journey” that you find in romance novels follows a basic structure.

So while the plot is happening, the lovers are meeting, pulling apart and/or being pulled apart, coming together finally at the climax, and earning their HEA (happily ever after) at the end.

With straight romance genre, there is just the one romance engine driving the story. But what can make it a strong story is that developed subplot, acting as a force for and against the lovers.

I’m not going to go long and far into romance, but some discussion of this genre is helpful to a lot of writers. I had to learn well this story structure when I sat down to plot out and write my first historical Western romance, Colorado Promise.

I’d had romantic elements and subplots in some of my novels (Time Sniffers, The Map across Time, The Unraveling of Wentwater), and some of them were key to the main plot. But those novels aren’t considered romance genre. They don’t fit that category, and they wouldn’t meet those readers’ expectations if I called them romance novels.

So in today’s post I’m going to start to lay out those next ten scene types (that go in alongside your foundational ten scenes) and show how a romance novel might be structured to work with that romance story engine.

Because many romance novels alternate between the hero’s and the heroine’s POV, this may seem like a no-brainer. Again, there are lots of ways you can do this, but I’ll show you one example. Your novel idea might call for some variation. And with a first-person novel, this of course is going to be different.

For the most part, a first-person novel is going to work best if it follows the basic 10-20-30 scene structure (which I’ll be sharing as we go along). For now, those first ten scenes are still valid across genre. So get those worked out in place, then allow yourself the freedom to play with the next ten.

Before We Go There . . .

This week, in preparation for sharing those next ten scenes that can be layered over the primary ten, let’s look a bit at the “Lover’s Journey” as so wonderfully explained by Hollywood screenwriting consultant Michael Hauge.

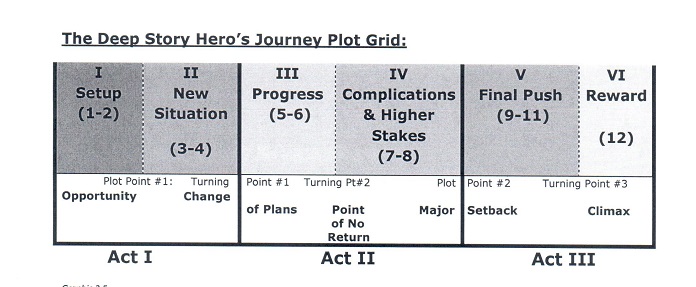

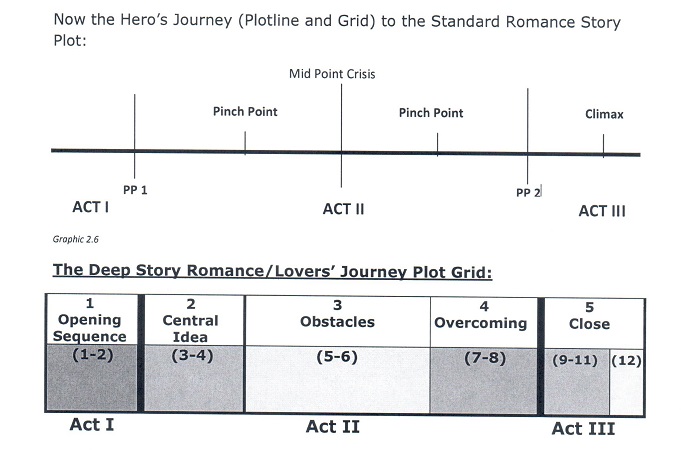

According to Hauge, there are some key differences between the classic “hero’s journey” and the “lovers’ journey.” Without going into volumes, let’s just say that the modern romance structure follows a specific development, and the bulk of the key scenes are in the last third (he uses the three-act structure) of the story.

Take a look at these two charts and you can see the comparison between the two journeys. The acts are delineated by the heavy vertical black lines.

Hauge proposes twelve key scenes in both the romance and traditional structure. Not every romance story has to have all of these, but they’re the milestones you’ll see in most romance novels. I often leave out two or three and replace with ones that work better for my story. NOTE: on the lower chart, those numbers in parentheses pertain to the scene numbers below. In other words, “The Dance” would occur near the end of the much-larger Act II in a romance novel.

If you’re thinking of writing romance, it will help you to work with these, and I’ll show you how these layer in next week—in general and with specific examples. In particular, since I’m now plotting out my fourth novel in my romance series, I’ll show you how I’m coming up with scenes using this template and method.

Here are the twelve romance scenes (in my wording):

- Ordinary World: We see the heroine’s normal world before she meets the hero.

- The Meet: The lovers meet.

- Rebuffed: Heroine has a negative response to the hero that shows they’re incompatible (or you can reverse all this and make this the hero’s reaction to the heroine).

- Wise Friend Counsels: Heroine’s friend/mentor points out why the hero is right for her.

- Acknowledge Interest: Heroine is forced to acknowledge her attraction to the hero.

- First Quarrel: Lovers have an argument or disagreement that pushes them apart.

- The Dance: Opposites attract and repel. Development of the relationship but with tension!

- The Black Moment: Romance is dead, impossible due to something that’s happened.

- The Lovers Reunite: They finally openly admit/accept they are fated/ meant for each other but things stand in the way.

- Complications Push Them Apart: Tension precluding the big climax, usually due the complications of the subplot.

- Together At Last: Working together, thrown together, at the climax to overcome the last big obstacle (emotionally and actually), they are finally together or joined in love and purpose.

- HEA: or happily ever after. The reward for the hard journey.

You can probably see how a few of these scenes are going to take the place of some of the ten key scenes (such as #1). Again, this is all flexible, and you can move things around and add in as your plot requires.

But, to me, the key here is first laying down those foundational scenes first. With romance stories, the subplot is key because if all you have are scenes showing the hero and heroine talking or walking in the park or arguing over something, you don’t have a story.

You need a plot! You need action, secondary characters, and the development of conflict, high stakes, and tension. In other words, you want to throw your hero and heroine into a big situation that can force them to ride that romance engine to the finish line.

Next week I’ll go into examples using the 10 Key Scenes chart and show you how a romance novel might utilize this structure.

Are you working on a romance novel or thread? What are your thoughts on these twelve key romance scenes?

Perfect timing. I need this structure to finish my first novel. I never realized how complicated writing a romance novel could be. Sort of like real life “romance”. 🙂

Glad this helps. Next few posts on this will give more concrete examples.

By the way, I’ve been reading your “Writing the Heart of the Story” and it’s a big help!

I just finished my sci-fi novel and I have two romance subplots in it. To me if you’re integrating romance into a non-romance book it doesn’t need nearly the number of scenes listed here. For example, in my book I use:

Ordinary World: We see the heroine’s normal world before she meets the hero.

The Meet: The lovers meet.

Rebuffed: Heroine has a negative response to the hero that shows they’re incompatible (or you can reverse all this and make this the hero’s reaction to the heroine).

The Dance: Opposites attract and repel. Development of the relationship but with tension!

Together At Last: Working together, thrown together, at the climax to overcome the last big obstacle (emotionally and actually), they are finally together or joined in love and purpose.

The main reason I don’t think a lot of them are needed is because the focus of a non-romance novel isn’t really the romance so there doesn’t need to be tension as far as a back and forth of love or not love, compatible or not, etc. You also don’t need a “happily ever after,” one of my subplots ends in disaster, but the love between them helps fuel motivations of the main plot.

Right, as I mentioned last week, many novels can have a romance engine in addition to a main plot engine, and it’s good to keep in mind that the best stories with a romance thread have conflict at the start due to the hero (or heroine) stuck in their persona. By the end, they get the gal or guy as a “reward” for coming into their essence. This is very popular in movies.