6 Cinematic Techniques You Can Apply to Your Novel Right Now

Many of us were raised watching thousands of movies and television shows. The style, technique, and methods used in film and TV are so familiar to us, we process them comfortably. To some degree, we now expect these elements to appear in the novels we read—if not consciously, then subconsciously.

We know what makes a riveting scene in a movie, and what makes a boring one—at least viscerally. And though our tastes differ, certainly, for the most part we agree when a scene “works” or doesn’t. It either accomplishes what the writer or director has set out to do, or it flops.

As writers, we can learn from this visual storytelling; what makes a great movie can also strengthen a novel or short story. Much of the technique filmmakers use can be adapted to fiction writing.

Break Scenes into Segments

Just as your novel comprises a string of scenes that flow together to tell your story, so do movies and television shows.

However, as a novelist, you lay out your scenes much differently from the way a screenwriter or director does. Whereas you might see each of your scenes as integrated, encapsulated moments of time, a movie director sees each scene as a compilation of a number of segments or pieces—a collection of camera shots that are subsequently edited and fit together to create that seamless “moment of time.” By thinking in terms of segments in creating each scene, writers can create a dynamic, visually powerful story.

So how can novelists structure scenes with cinematic technique in a way that will supercharge their writing? Here are six steps that will help you structure your novel as if you were a filmmaker:

- Identify key moments

Think through your scene and try to break it up into a number of key moments. First, you have the opening shot that establishes the scene and setting. Then, identify some key moments in which something important happens, like a complication or twist, then jot those down.

Then write down the key moment in the scene—that “high moment” I always harp on—that reveals something important about the plot or characters. That should come right at or very near the end. You may have an additional moment following that is the reaction or repercussion of the high moment.

- Consider your POV

Now you have a list of “camera shots.” Think of each segment on your list, then imagine where your “camera” needs to be to film this segment.

Remember, you are in a character’s POV—either a first-person narrator telling and experiencing the story or a third-person character in that role. So consider where that character is physically as he sees and reacts to the key moments happening in your scene.

You now have your “direction” so that you can write this scene dynamically. Come in close to see important details. Pull back to show a wider perspective and a greater consequence to an event.

- Add background noise

Consider what sounds are important in this scene. They could be ordinary sounds that give ambiance for the setting, but also think of some sound or two that you can insert into the scene that will stand out and deepen the meaning for your character.

Church bells ringing could remind a character of her wedding day as she heads to the courthouse to file divorce papers. Birds chirping happily in a tree next to a grieving character can sound like mocking and deepen the grief.

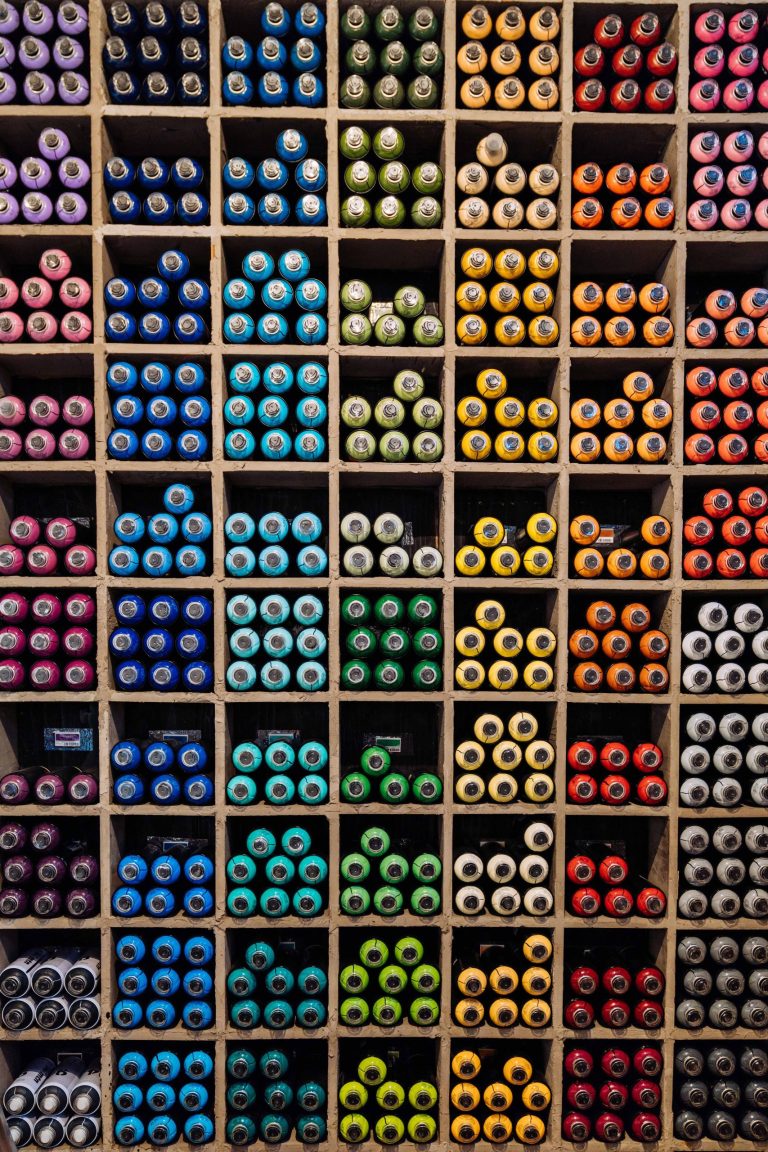

- Color your scenes

Colors can be used for powerful effect. Different colors have strong psychological meaning, and filmmakers often use color very deliberately. Red implies power; pink, weakness. You can “tinge” your scenes with color and increase the visual power. Color can also add symbolism to an object or be a motif.

Want to learn more? A great book to read is Patti Bellantoni’s If It’s Purple, Someone’s Gonna Die.

- Think about camera angles

The angle of a “shot” also has powerful psychological effect. A camera looking up at a character implies he is important or arrogant or powerful or superior. A camera looking down implies someone who is weak or inferior or oppressed or unimportant.

If your character is in a scene with others and feels superior, you might have him elevated or being seen from below to emphasize this. A woman being fired might be sitting in a chair with the boss standing over her. These little touches add visual power.

- Include texture and detail

Consider adding texture. Too often, novelists put their characters in boring settings, without saying where they are, what time of year it is, or what the weather is like. We exist in a physical world, and movies showcase setting and scenery in great detail.

Add texture to your scene by infusing it with weather and sensual details of the surrounding area. The feeling of the air in late fall in the middle of the night in Vermont as two characters walk through a park is texture the reader will “feel” if you bring it to life in your scene.

Novelists who think like filmmakers can create stunningly visual stories that will linger long after the last page is read. Spend some time using a filmmaker’s eye to take your scenes to the next level, giving them dynamic imagery and sensory details as well as deliberately placing characters, colors and sounds in your scenes for targeted psychological effect.

If we want to move readers emotionally by our stories, the best way is to bring our novel to life by using cinematic techniques.

Which of these 6 cinematic elements do you like best? Which one could you grab right now and use in the scene you’re presently writing? Share about it in the comments!

For a deep look at how novelists can use cinematic technique, get Shoot Your Novel. No other writing craft book teaches writers how to segment their scenes the way filmmakers do, using camera shots and cinematic devices to create powerful scenes and evoke emotion.

For a deep look at how novelists can use cinematic technique, get Shoot Your Novel. No other writing craft book teaches writers how to segment their scenes the way filmmakers do, using camera shots and cinematic devices to create powerful scenes and evoke emotion.

The most effective way to write scenes is to show, not tell, and this highly acclaimed book will give you unique tools to load your writer’s toolbox with.

With Shoot Your Novel, Susanne Lakin does something wonderful and unique. While lots of us in the business of helping writers and storytellers recommend adding vivid images to scenes, Lakin goes much further to reveal how employing the tools and techniques of movie directing, editing and cinematography will give your fiction deeper meaning and greater emotional impact. Her book is an essential tool for any serious novelist.

—Michael Hauge, Hollywood screenwriting coach, author of Writing Screenplays That Sell

Happy Holidays! Interestingly, this post comes right after I’ve been dealing with a specific “cinematic” issue in my historical fiction series that’s touched on in this great post, but with a slight twist for me. Briefly, I like to use “camera shots” to structure my paragraphs, or as Rad Bradbury says (paraphrasing): each graph is a camera shot, and when the camera moves (or the edit occurs), a new graph starts. This is pretty obvious with dialogue but is no less important in narration/description (to me). I’ve had editors and beta readers not agree with me on this because I tend to have lots of short graphs, but that’s the style that makes sense to me. Cinematic. Filmic. And I know it’s the right path for me after an old friend (who works in Hollywood), read my first novella and commented: “your writing is very cinematic.” Bingo!

Nice! Do you mean each paragraph is a shot? I wouldn’t say that, since you may need to keep your camera in one “place” for many pages. But I’m glad all this helps!

For me, each paragraph is a shot (or shift in focus, idea, time, tone). My longest paragraphs are in the 6 sentence range. I really don’t like long paragraphs. And because I’m writing shorter works (novellas basically), things need to move right along. But this is a great topic and conversation! And I guess I better get your “Shoot Your Novel” book, eh? 🙂

My favorite technique is the texturing of a scene with details that make the place look real when you read it. I’m currently revising my novel, and whenever I read the opening scene I am there. It is so visual in content; from the cold, leaden November skies, to the rain that the protagonist is walking through, to the bloody colored clay mud running from a road cut under a tree that has all but lost its roots to erosion, to the bitter green odor of torn honeysuckle vines grubbed away from an aging stone wall. Wonderful stuff for applying the shading to a word picture.

Nice!

I can use number three, four, and six. In my MC’s ordinary world, he is leaving his office with big plans of proposing to his lady friend. He is going over the anticipated even while he shuts down for the evening. There is a storm raging for his trip home. Lightning is flashing and thunder is crashing (3.) His office light is off accept for the light of the lightning flashing through the window. Dark and sporadic light from the lightning (4). He thinks of his walk to the car in the pouring down rain as the wind whips the rain sideways and he walks through the puddles. I have purchased your book, “Shoot Your Novel” which I will revisit when I finally begin writing the story. I have the story outlined (Hero’s Journey) and have 3/4 of the scene/sequel scenes constructed.

Thanks for your blog and for sharing your knowledge obviously paying it forward from your writing mentors.

JW