Brilliant or Boring? How Do Your Characters Measure Up?

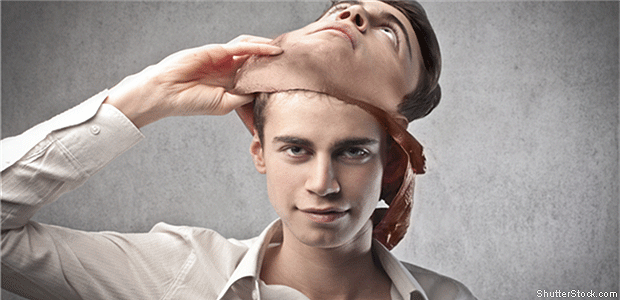

When critiquing manuscripts, I often wonder how much time writers spend thinking about the personality types of their characters. Because so many characters are either stereotyped, shallow, or boring.

I’ve written a lot about characters and explained that ordinary people are boring. While we want to populate our stories with believable characters, we should avoid ordinary and boring—at least with our protagonist. You might have a minor character who is irritatingly boring to your protagonist, and that character might have a great role in the story.

But you don’t want to bore your readers with flat, uninteresting characters. I hope you can see the difference.

What’s “Larger Than Life”?

You may have heard that fiction writers should create characters who are “larger than life.” That’s a bit puzzling because in life there are all types. How is one “larger” than another? And you don’t want to go to the extremes of hyperbole or exaggeration with all your characters. If you do so, your novel will be a parody of life, not a slice of life (though, if you are aiming for parody and great humor, that’s fine).

In other words, fiction writers need to find a way to craft characters that aren’t boring or ridiculous but are still intriguing and compelling to read and care about.

We looked at two important facets of a character: motivation and wound. This week I want to explore personality.

I think this is a hard one for writers—very challenging. We see so much generic around us, it’s not easy to come up with unique personalities for our characters.

And before you can craft those unique personalities, you have to determine what types of characters you need to populate your story and what actions they’ll be doing. Then you have to give them a personality.

Ask yourself what role a particular character plays in your story. Ally, romance interest, nemesis, mentor, big sister? Every primary character in your story should have some important impact on your protagonist, for good or ill.

With any “type” or archetypal character, we tend to default to stereotype. If we’re writing a thriller, our hero is often a strong, muscular, square-jawed rough-edged man who has a military background and is afraid of nothing. The heroine of our romance is curvaceous and gorgeous (especially if the author is male—from my experience), not just practically perfect in every way like Mary Poppins but actually perfect in mind and body.

Really, this kind of typecasting sabotages our fiction. But unless you have some guidelines to go by, it can be hard to come up with great personalities for your characters. So let’s consider some guidelines.

How Premise Weighs In

Your genre may inform some of the requisite characteristics, but even within the bounds of genre you can still develop fresh, unique characters. Your readers deserve those elements of originality, so spend time on your characters and resist the default mode. And really, what’s more important is your premise.

How does premise come into play here? Your premise lays out the situation your protagonist has to tackle. If you’re writing a novel about a group of scientists that are trapped in an orbiting space station and have to find a way to survive for three years before rescue comes, you first think about the skills and expertise those characters need to have.

I wish I didn’t have to say this, because isn’t it obvious? I see so many characters thrust into roles that they are wholly unqualified for. Characters cast as cops or doctors or investigators that have no smarts, no skills, no training. Characters who are presented as top litigators who can hardly utter an intelligent sentence.

While the real world does shock us with the level of incompetence and immaturity we see, for example, in our political realm, unless we are doing a spoof or sick comedy, it’s best to stick with the expected. It’s just more believable to have competent characters doing things that require expertise.

Ask questions of each of your characters. If you have a female captain of a space station, and she’s your main character in your suspenseful drama—the one who, in essence, saves the crew by her wits—she’s going to have some smarts.

Inner and Outer Conflict

Okay, but what else? The main component that drives a story is conflict, so once you determine what she’s good at and the training she’s had, think about the conflict she might deal with. This goes for both inner and outer conflict. This also speaks to the themes you want to bring out.

The wound you give her can provide that strong inner conflict. But you can compound that with her personality aspects. She could have an impatient personality. Or maybe, because of her wound, she struggles with self-doubt. Her parents could have verbally beaten her down so that she is always trying to prove herself, and nothing she ever does is good enough—for her. This might make her competitive, short-fused, overly critical of others, or jealous of another who excels or surpasses her in job promotion.

What kind of outer conflict have you come up with for your story? Nearly every novel benefits from interpersonal conflict. No one is perfect; we all rub abrasively against another from time to time. Creating characters that bring out both the best and worst in one another makes for strong, exciting stories.

When you think about motivation and core need, aim for making characters clash. If your female scientist protagonist has a strong motivation to control those around her and a core need to prove herself, she is going to clash with other characters whose motivations are to go rogue and depend on their own wits to survive or who, being male, have a wound that make them buck a female in authority.

If you start with your protagonist—her wound, her needs, her past that forms her, her education and upbringing, her quirks and foibles, you can then come up with some other cast members who could be a source of irritation and inspiration to her.

Think “Opposites”

Putting your characters in a crucible of fire brings out hidden insecurities and fear-triggered behaviors that may not normally be seen in the day-to-day routine. What weaknesses can you give each of your characters that pop out when they’re under stress?

But what about when they’re not under duress? You can still create a cast of characters who clash, and thus provide an undercurrent of continual conflict and tension.

Think “opposites.” A loud, talkative character may annoy or intimidate a meek introverted character. If they have to work together under stress to get something done, some tension will arise.

Elizabeth George, mystery writer, does a great job in pairing the rich, high-class Inspector Thomas Lynley and his “sidekick” Sergeant Barbara Havers, who comes from a lower class and whose speech, habits, and manner irritate her partner at the Yard.

Spend Time Crafting Your Cast of Characters

It’s helpful to make a list of potential supportive characters for your novel, all centering on the protagonist and her goal. Your antagonist can also have a supporting cast.

With my historical Western romance novels, I try to come up with two to three secondary characters that are in close orbit to both my protagonist and antagonist.

For example, in Colorado Dream, my hero, Brett, is a cowboy out on the range, driving cattle and tasked with helping discover the culprits involved with a cattle rustling operation. I came up with two supporting “sidekicks” for him—Archie, a young greenhorn about sixteen years old who doesn’t know a thing about being a “puncher” and who gets picked on by some mean old-timer cowboys. In addition, I gave him an ally who is an experienced hand, like Brett—a loyal, honest straight talker. Since Brett struggles with a troubled past and harbors guilt over abandoning his abused mother, I made Tate Roberts easygoing and upbeat to counteract Brett’s tendency to brood. He provides Brett with the encouragement needed to press on and not slip into despondency.

By including small scenes showing Brett interacting with Archie (which provide both high drama and comic relief) and with Tate (which provide insightful introspection that helps with Brett’s character arc), I am able to play out the plot via the differences in their personalities.

My antagonists in this novel are not just the two mean cowboys that pick on Archie (and turn out to be the cattle rustlers that Brett and Tate catch) but also a rich rancher whose son became paralyzed when Brett shot at him (in defense) and caused him to fall off his horse. Here, too, I gave this antagonist two sidekicks—ranch hands that Orlander, the rancher, sends out to find Brett to kill him.

And here, too, I thought about personality opposites to make these thugs clash. One is slow and thoughtful, an older fella whose conscience is greatly troubled—because he knows Brett is innocent, and he, along with his buddy, lied to Orlander about what happened. The other ranch hand is bossy and unprincipled. He just wants to find Brett and give him his comeuppance. He has no scruples. These personality characteristics come into play in the climax, when they face Brett head-on at the big ranch party.

Opposites. That’s the ticket for good drama and conflict.

And that’s the point I’m leading to. All these characters with their personalities are developed with one keen purpose—to serve the plot. They aren’t just random “diverse” attributes thrown into the story to give a variety of personality types. Which is the method used by my writers.

This is why I cringe when I read how some writers skim through Myers-Briggs personality classifications and just pick and choose characteristics like picking ice cream flavors.

It’s the premise and the plot development that should inform the characters and their personalities.

So if you start with your premise and your protagonist’s goal, crafting a strong, unique personality for your main character before all else, giving her a wound and inner motivation that is a mix of past experience and character traits, you can then brainstorm your cast of supportive characters.

Think of a part each character can play in your story—a part that impacts your protagonist for good or ill. Think of the kind of personality that will both fit the “type” (ally, antagonist, wise adviser, etc.) as well as provide some contrast to your protagonist. Read my numerous posts on archetypes to see what kinds of personalities might work in your story.

Think conflict. Think opposites. Think “clashes.” Then, I think, you’ll come up with some personalities that will transcend the stereotype and avoid the “boring and ordinary.”

What two characters in your novel or one you’ve read provide great opposition and clash with each other? Share why this helps play out your plot and premise.

Want to craft great characters? Check out the online course: Your Cast of Characters

Learn all about creating the perfect cast for your novel in this new online video course. The course launches MAY 1, 2020, but you can enroll now and get $50 OFF the regular price by using coupon code EARLYBIRD. Sign up HERE at my online school. Remember: you CANNOT access any of the modules until May 1. I’ll be sending you an email at that time to let you know the doors are open!

Your characters are the heart of your story, so be ready to learn a lot of great tips. BONUS! Included in your course are interviews with best-selling authors, who discuss their process of how they come up with the best characters for their stories. You can’t find these videos anywhere else but in my new course.

Your characters are the heart of your story, so be ready to learn a lot of great tips. BONUS! Included in your course are interviews with best-selling authors, who discuss their process of how they come up with the best characters for their stories. You can’t find these videos anywhere else but in my new course.

And remember: you have lifetime access to all my courses at cslakin.teachable.com, and you also get a 30-day money-back guarantee, always. I want you to be happy with the content you are learning. So …. no risk! And check out all my other online courses while you’re at it. Thousands of writers have taken these courses around the world and sing their praises.

Here’s some of what you’ll learn in this extensive course:

- What the basic types of characters are and what roles they play in a story

- How your plot and premise inform the characters you develop

- How to determine if a character is essential to your plot or just “filler”

- What kind of supportive characters does your specific story need and how you can determine that

- How to create characters that act as symbols

- What archetypes are and how you can utilize them to create fantastic characters

- How incidental characters can make or break your story

- Why understanding character motivation is paramount

These video modules feature numerous excerpts from novels, movie clips, and deep instruction. In addition, you are given assignments to help you develop a great cast of characters which you can download and do over and over as needed. Be prepared to learn!

Appreciated your article!

“I see so many characters thrust into roles that they are wholly unqualified for…”

I’ve seen that, too. But, for me, I love creating characters who believe lies about themselves, lies that tell them they aren’t qualified, that they’re only going to fail. Then, when thrust into dangerous or testing situations, often multiple times, they eventually learn that they are up to the task. Readers see through the character’s misconceptions and begin rooting for them to succeed and everybody is happy when the victory is finally achieved.

I totally agree! What I decry is when writers show a totally untrained, naive, stupid, and/or immature character in a role that requires serious expertise and maturity. There is a huge difference!

Very helpful post — what I’m taking away is to consider how each character affects the heroine, and to consciously identify the supporting characters for heroine and villain. Your examples really help me see how this will work. Thank you!