Getting into the Layering Frame of Mind

Do you do this? Maybe you have an idea how your novel will start. You might also picture the climax scene and the ending. Then, you possibly have some great ideas for scenes showing conflict or some plot complications. But this isn’t the same as starting with a list of needed scenes and brainstorming to design those scenes to frame your story.

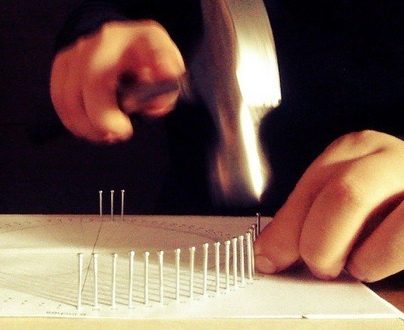

Framing is everything. I often liken writing a novel to building a house. I talked about this last week. If you want a sturdy, well-built house, you can’t just cut a bunch of neat-looking two-by-sixes and start hammering. You need a strong framework built on a solid foundation. Once you have that, you can proceed to the next tasks, like running electrical and nailing siding.

I go into great depth in my book The 12 Key Pillars of Novel Construction to show writers what the major novel components are and how to build them. But that’s not what we’re talking about here. This is about the body of your scenes and how to puzzle-piece them together the best way—by layering.

I’ve done a lot of stud-cutting and framing houses with my contractor husband, and I can say that building a house is akin to layering, one layer at a time. You can’t put the roofing material on a house that hasn’t been sided yet and doesn’t have roof trusses. Ain’t gonna happen. Everything goes in at the right time and in the right place.

Why should novel construction—or building anything, for that matter—be any different?

Get into the Layering Frame of Mind

So, the sooner you start thinking of building your novel in a layered way like that, the sooner this daunting task of novel-writing will become easier. Maybe not easy—because novels are highly complex animals. But why not make the effort as streamlined and approachable as possible?

My new and simple approach to grasping and mastering novel structure may not be all that new. Yet, I’ve never seen anyone teach or use this method just this way. I may possibly blast a few things you’ve been taught into smithereens. I’m hoping to rattle your cage a little and get you thinking in some new ways.

I see too many stuck writers. They have a head full of great scene ideas for their novel but just can’t figure out what to do with them. They lay out their scenes as randomly as a person might shuffle a deck of cards and then throw all the cards onto the table and call it good.

It’s not good. It’s a disaster.

I use this specific layering method now for all my novels. I start with the premise and one-sentence story concept. From there I get those ten key scenes figured out. After that, I start layering the next level of scenes. In my upcoming book Layer Your Novel, you’ll see differing ways you can layer, but this method, in general, works for any and all genres.

The purpose of using a “staged” or multilevel process is to help you flesh out that basic story idea you have and build a solid story. If you use this method in conjunction with building your twelve key pillars (your novel’s individual components or “building materials” as detailed in The 12 Key Pillars of Novel Construction), you will have the blueprint you need to write a great novel.

Having a step-by-step instruction guide to building a novel is something I wish I’d had thirty years ago when I was biting off every nail trying to figure out this crazy business of writing fiction. I’m hoping, with this book, and the other books in my Writer’s Toolbox Series, you won’t needlessly suffer as I did.

Writers who’ve been using my Ten Key Scene chart and referencing all my blog posts on this layering topic have been raving about this method, so I’ve gone ahead and pulled all my blog posts together, along with much additional material, and created this book. I’m confident you too will benefit greatly from layering your scenes.

A General Overview of Novel Framework

It’s so important to understand that most novels (except epic stories that cover decades, such as a biography or family saga) are about a character going after one short-term goal.

Being clear about your protagonist’s goal is paramount when it comes to structuring your novel. Why? Because without that goal as the heart of your premise, your story will be flawed. You need to build everything around the goal. This is true for movies and plays and novels.

Once you’ve figured out where to start your novel, based on that inciting incident at the start of your story, you then have these other sections:

- The 25-50% section is the “Progress.” This is where the protagonist makes progress toward his goal. Many screenplays follow this specifically, to the second, and movies do well sticking to this very expected formulaic structure. But I don’t feel you have to force novels into this framework so fanatically. Novels really are different beasts than films and can succeed with creative or flexible structure, so don’t get your shirt all bunched up trying to force your story into that round hole if it’s got some sharp edges.

- The 50-75% section presents bigger and bigger complications and obstacles as you approach the climax, which falls anywhere between the 75%-99% region. Again, it depends on the story. Hauge uses the movie Thelma and Louise as an example of a climax coming right at the very end of the story (the 100% mark). Every story will have its “perfect” place for the climax.

And, depending on your plot, the resolution to the whole shebang will fall at the end of the book, with (hopefully) a brief wrap-up. I go with the motto “Quick in, quick out,” and that’s what I teach my editing clients. The best novels end quickly after the big climax, which is where the protagonist either reached or failed to reach her goal. Since that’s the point of the story (to see if the goal is reached), it does a writer no good to wander off into a whole bunch of new plot developments at the end of the book.

I’ve critiqued novels that have another fifty pages of inconsequential story bits that have nothing to do with the premise of the novel or the protagonist’s goal.

Try Laying Out Index Cards to Get a Feel for Sections

Don’t just break up a story or create parts to a novel randomly or because someone tells you it’s a must. Fashioning your story into sections is extremely helpful, and it’s something you can do even if you don’t label them as such for your readers.

Sometimes, after I’ve put all my scene ideas on index cards (as many as I can think of for my novel I’m about to write), I’ll lay them all out on my dining table. Usually I have between thirty and fifty scene ideas before I start writing my general outline.

Once I have all these cards in front of me, I’ll start laying them out in vertical rows. When I get to the place where it feels I’ve built up to a key plot development that presents “a door of no return” for my protagonist, I’ll start a new row with the next scene card.

It’s only after I do this that I learn how many “acts” I have.

It takes experience to know what these big “doors” are and where they should come in a story. And of course, as you get closer to the climax, there are going to be all kinds of complications. So how do you determine where an act “officially” ends?

There are lots of methods to this as well, and there are plenty of books and blog posts that can give you ideas. I find James Scott Bell’s Plot and Structure a great book to start with, which focuses on the traditional three-act structure. And for the most part I feel it’s good for beginning novelists to start there. But just don’t get locked into three acts because you’ve heard you have to.

I wrote a bit about this last year, so if you want to read more on act structure (and why you don’t need to use three acts necessarily), read this post and this one too.

Can you identify the main sections of your novel: inciting incident, the goal set, the progress, the build to the climax, the resolution? What part is hardest for you to lay in?

Can you identify the main sections of your novel: inciting incident, the goal set, the progress, the build to the climax, the resolution? What part is hardest for you to lay in?

I just wanted to comment on at least one of your blog posts. You have helped me so much with working out my story. You don’t even know. Thank you.

Thank you for this insight, Susanne. I’ve shared it online.

The inciting incident in my memoir about attending college as a mother of 5 was when the guidance counselor told me my oldest daughter shouldn’t go to college. She should stick with special ed classes. She wanted to attend college, and I was determined that she should have the opportunity.

The goal of my memoir is to complete college myself in order to help my children. I end up winning scholarship to the Ivy League after community college accolades.

The middle part about making sure each scene moves my own personal struggles to achieve a college diploma and why it’s important to me at each stage is the difficult part.

Pantsing loses its luster when you manage to come up with a lucid, knockout story line without a single word of text to your name.The “discovery” process is the same, the characters still hijack the story line occasionally (creating better prose than I can,) and the excitement remains. No going back from a well-constructed tale…