Masterful Narrative Scenes in Novels

Show, don’t tell. Yeah, we know that’s the rule. But there are times when scenes can be masterfully told by the POV character. Sometimes a character is telling a story, relating a memory, and if done well, it’s just as gripping as if the scene were played out in cinematic fashion.

I haven’t seen much written on the “narrative” scene, but this is a technique that suspense writer Lisa Gardner excels at. While narrative scenes can be in first or third person, the most effective ones I’ve read are in first person. What makes for great narrative scenes is the character voice.

In fact, the lack of that voice would risk boring readers. To me, openings of many best sellers (which we’ve examined in many of the First Pages of Best Sellers series on this blog), which are mostly narrative, are plain boring. And that’s because they lack a strong POV character voice.

We looked at some excerpts from Ron Hansen’s novel The Assassination of Jesse James and noted how his writing style or author “voice” made the narrative riveting (at least to me).

These are two different things. You may have an overall writing style like Hansen’s that infiltrates every page such that the only times you really get the “character voice” is in the dialogue. The storytelling voice can be consistent throughout a novel and set a specific tone or patina over the story. Hansen’s book, as I noted, reads like a biography, and I believe his choice of this stylistic voice was deliberate, to give this effect.

With most contemporary novels, however, we see the character voice prevailing in the narrative. And this helps readers get deep into point of view to emotionally impact them.

Take a look at Lisa Gardner’s opening to Right Behind You:

Had a family once.

Father. Mother. Sister. Lived in our very own double-wide. Brown shag carpet. Dirty gold countertops. Peeling linoleum floors. Used to race my Hot Wheels down those food-splattered countertops, double-loop through ramps of curling linoleum, then land in gritty piles of shag. Place was definitely a shit hole. But being a kid, I called it home.

Mornings, wolfing down Cheerioes, watching Scooby-Doo without any volume so I wouldn’t wake the ‘rents. Getting my baby sister up, ready for school. Both of us staggering out the front door, backpacks nearly busting with books. . . . [more description of daily life]

Then off [Dad] would go. And my mom would appear from the hazy cloud of their bedroom to start dinner. Or the door would never open, and I’d get out a can opener instead. Chef Boyardee. Campbell’s soup. Baked beans.

My sister and I didn’t talk those nights. We ate in silence. Then I’d read her more Clifford, or maybe we’d play Go Fish. Quiet games for quiet kids. My sister would fall asleep on the sofa. Then I’d pick her up, carry her off to bed.

Gardner spends the first pages of this opening narrative scene setting up the family situation. We see that Telly, the brother and narrator, is living in poverty with messed-up parents, and that he is basically the caretaker of his little sister, Sharlah, whom he loves dearly. He details Dad’s drinking and Mom’s drugs, and how he and his sister began to live in terrific fear. Once all this is set up, watch what happens:

Sister took to sleeping in my room, while I sat by the door. ‘Cause sometimes, the parents had guests over. Other boozers, druggies, losers. Then all bets were off. Three, four, five in the morning. Locked doorknob rattling, strange voices crooning, “Hey, little kids, come out and play with us. . . .”

My sister didn’t giggle anymore. She slept with the light on, ragged copy of Clifford clutched in her hands.

While I kept watch with a baseball bat balanced across my knees.

Then, morning. House finally quiet. Strangers passed out on the floor. As we crept around them, stealing into the kitchen for the Cheerios box, then grabbing our backpacks and tiptoeing out the door.

Rinse, spin, repeat.

Repeat. Repeat. Repeat.

Had a family once.

But then the father drank or shot up or snorted too much. And the mom started to scream and scream and scream. While my sister and I watched wide-eyed from the sofa.

“Shut up, shut up, shut up,” the father yelled.

Scream. Scream. Scream.

“F***ing bitch! What’s wrong with you?”

Scream. Scream. Scream.

“I said, SHUT UP!”

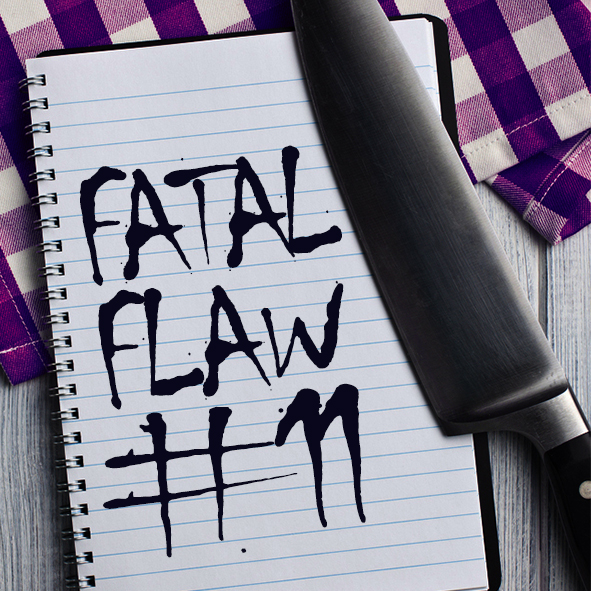

Kitchen knife. Big one. Butcher knife, like from a slasher film. Did she grab it? Did he? Don’t remember who had it first. Can only tell you who had it last.

My father. Raising the knife up. Bringing the knife down. Then my mother wasn’t screaming anymore.

The scene continues to play out in action, in “show, don’t tell” cinematic fashion. We watch what transpires and what Telly and Sharlah do to survive. The brilliant narrative scene ends (I’ve already showed too much—read this for yourself!) with this:

Had a family.

Once.

From there, the novel “begins,” with the present setup of the story, eight years after this tragedy, as a murder investigation begins that reveals connection to this earlier event in Telly’s life.

I hope you noticed some things as you read the passage. The character is telling this story as preface to the novel (Telly’s scenes scattered throughout the novel are in this same first-person type of narrative, and he is not the protagonist), and his voice is unique and strong.

I hope you noticed some things as you read the passage. The character is telling this story as preface to the novel (Telly’s scenes scattered throughout the novel are in this same first-person type of narrative, and he is not the protagonist), and his voice is unique and strong.

It’s unique in the diction and sentence structure. It’s permeated with his attitude, which is detached, hinting at the emotional trauma this event fomented. At one point he refers to “the father” and “the mother,” as if they are not his. As if he doesn’t know them. This is all very deliberate and artful.

Instead of playing out the scene when it happened, we get Telly’s current emotional take on it, eight years after the incident, which is important—for he is a character in the present day of the story, and his perspective on life, what happened, and his sister is essential.

If Gardner set the scene eight years prior, with Telly’s perspective and young voice appropriate to that time, it would not give insight into his attitude these many years later. And it would do one other thing, which would (to me) ruin the suspense: show what Telly was thinking back then about his and his sister’s actions. And that needs to be kept secret until the climax of the novel. That’s the hook that drives the story—why Telly did what he did and what his motive was at the time.

We novelists have it so ingrained in us to “show, don’t tell,” but there are times when having a character tell a story is exciting and mesmerizing. Gardner didn’t just summarize the event; much of the scene is played out with action and dialogue.

Maybe this will give you ideas on how you might use masterful narrative technique like this in your novel.

Any thoughts about the “narrative” scene? Do you find this opening to Gardner’s book engaging? I highly recommend you get her novel (HERE), and check out her other books too. I loved Hide, which I’ll share a bit from in a future post.

Hi there Susanne. I was entranced by this opening and what the narrator didn’t say was also powerful. Hinting at unspeakable things allows the reader to immerse themselves in those places. Perhaps filling the gaps using their own experiences or perspective drawn from other forms of narrative lived or learned. Also, I did have a look at Ron Hansen’s book and was impressed by his narrative style. John Steinbeck also did a great job on using narrative POV to immerse the reader. Oh but if there were time to read all the wonderful books out there!

This beginning is descriptive, chilly, almost reportage. It is well enough written, gets the job done without superfluous details.It is filled with fragments, memories also tending to be fragmented. I do not find this beginning entices me to keep reading based on voice. The killing interests me, but truthfully, I find the choppiness of the diction kind of annoying.

This is Telly’s voice and is very authentic for his background and character. I find it terrific because it gives texture to this troubled kid and it sounds believable, a compelling way to tell what happens that night.

I’m working on a project right now where the main character wakes up in a strange place. I’m conveying emotion along with description of what he wakes up to. Telling mixed with emotion is an interesting combination. My first in doing so. Thank you for this. It leads me to believe I’m on the right path.

very good article