Showing Your Scenes through Your Characters’ Senses

One of the reasons readers willingly immerse themselves in a story is to be transported. Whether it’s to another planet, another era—past or future—or just into a character’s daily life, readers want to be swept away from their world and into another—the world of the writer’s imagination.

It’s challenging for writers to know how much detail to put in scenes to effectively transport a reader. Too much can dump info, drag the pacing of the story, and bore or overwhelm. Conversely, too little detail can create confusion or fail to evoke a place enough to rivet the reader.

In addition to knowing how much detail to show, writers have to decide what kind of details to use. I often read scenes in the manuscripts I critique, for example, that have characters engaging in lots of gestures, such as rubbing a neck, bringing a hand to a cheek, pushing fingertips together, turning or moving toward something—all for no clear reason.

Showing body movement, gestures, and expressions can be an effective way to indicate a character’s emotional state, but this needs thoughtful consideration so that the gesture or expression packs the punch desired.

I’d like to speak to the importance of showing setting—and not just showing it in any old way. What is key to creating a powerful setting is to show it through your character’s POV and in a way that feels significant.

Showing Significant Settings

When is setting significant to the reader? When it’s significant to the character.

That’s not to say every place you put your character has to evoke some strong emotion. A character who goes around gushing, crying, or jumping in excitement over every locale will appear to be missing some marbles.

But just as in real life, places affect us—some more than others. Each of us can think of numerous places in our past that bring a flood of emotionally charged memories. Showing setting colored by a character’s emotions is not only effective and powerful, it also captures real life.

But let’s talk about those other settings. The ones that aren’t emotionally charged. The many places in which you set your characters to play out your scenes. Some of those places are merely backdrops, places your character traverses daily or on occasion. They’re not important, right?

Let me just pose this possibility: even though you’ve thought a bit about the locales for your scenes, it may be that you aren’t truly tapping into the power of setting.

Bring the Setting to Life

You may need to write a scene that shows a tense discussion between two characters. So you stick them in the coffee shop, since it doesn’t matter where you put them. And, hey, a coffee shop makes sense. Everyone goes to them. It shows the characters doing ordinary things.

Sure, put your characters there (but please not twenty times in a novel). Or do something more interesting. I encourage writers to try to think up original, unique settings that bring a character’s bigger world—town, city, region—alive. But even if a writer thinks up fresh and creative locales in which to place her characters, those settings might still come across in a boring, ineffectual way.

But it’s the conversation that matters, the writer argues. That’s what I want readers to pay attention to. The setting is just a backdrop.

In many scenes, that may be true. But if a writer wants to transport her reader, she’ll think about bringing the setting to life via sensory details—which are observed by the POV character.

Let’s take a look at a Before and After to see the difference between setting that is just “a backdrop” and setting brought to life by being shown through the character’s senses.

Before:

On the fifth morning after the council meeting, about an hour after the late autumn sun had risen over the mountains to the east, the group of seven met at the base of the village. After the meeting, they had come to a consensus that they would travel together for as long as possible. Though some were still sick or wounded, they would delay no longer. They had been treated well and shown honor in Haknoor, but they were strangers and didn’t fit into the routine of the closed community. Rhianna also realized that they were a burden to feed, for the resources of Haknoor were already stretched by the arrival of refugees. In any case, most of the companions were eager to return to their own homes, and to whatever family they still had. Even Grubb, who would not walk again for many weeks or months, was as eager as any to depart, though he did not speak much. “I feel trapped,” he confided to Rhianna. “I do not want to be a burden on the journey, yet neither do I want to be a cause for delay.”

Angor was the last to arrive. Rhianna had not seen him at all during those two days. She heard from the others that he had been in the mountains above the village helping mine the precious jewels the Haknoor people treasured.

As they loaded and double-checked their packs, they once again discussed their plans for travel. Three of their group were traveling north, returning to their own homes and villages. They had the shortest distances to go. The best route home for the other four also began in the same direction for the first few days, then veered more eastward along the trade road. The trade road passed the southern shore of Tule Lake and the easternmost of the Haknoor villages before beginning its descent alongside the Marsh River and down into Wildwood and the nearby desert. Eventually it led to Wildemere, the main city of Wildwood and the only large inland settlement in the region. Passing through Wildemere would take the travelers perhaps half a day out of their way farther west than they wanted to go, but they had agreed to the plan.

“We should float home on the Tule River,” Valdon suggested, when he learned that it passed through the hills less than a day’s journey away. Though his knee had recovered somewhat from the battle, he was still moving about with a limp and did not feel fit for hard travel. “Save us all the walking through this blasted wilderness. The river would bring us almost to our doorstep.”

Rhianna laughed, thinking Valdon was joking. When she realized the warrior had been serious, she explained why it was not a good idea. “That way cannot be traversed. The Tule Falls is but one of a dozen waterfalls in the canyon that would crush you, and even if we could build boats, there would be no way to portage them around the falls.”

Valdon sulked but consented to the long walk home. He did not wish to wait until his knee was fully healed.

Rhianna hefted her pack and started along the wide rutted road, the other six following her lead.

So boring. There are a lot of details about the locale of this scene, geographically, and it seems to indicate Rhianna is the POV character, but her presence as the voice of this scene is minimal. Without connecting her to the setting, and without bringing out sensory detail, it’s hard to get a feel for this place. And as a result, it’s hard to care at all what these characters do—whether they head north or even fall to their deaths over Tule Falls.

So much more comes into play in a scene—the POV character’s present needs, motivation, mind-set, physical and emotional condition, and goal or objective. But even if those things were brought out, if the setting were still just a backdrop, the scene would feel deficient.

Let’s take a look at an After version, in which I attempt to show the setting through Rhianna’s POV instead of tell about it in a dry, impersonal info dump.

After:

Rhianna stood on the jagged ridge of sharp lava rock and watched the late autumn sun peek above the horizon. The waft of warm air coming from the sun’s rays did little to dispel the ache in her heart. Though the morning’s amber glow seemed to set fire to the rolling hills that spread out before her, the chill in her bones sat heavy—a damp fog of pain full of the memories of her slain companions.

Already the others were gathering at the gates of the village. Even five days after the council meeting, where they’d come to a consensus that they would travel together for as long as possible, some were still sick or wounded, but they would delay no longer. Rhianna yearned for home.

The smoke from cook fires drifted to her, hinting of meats and sage and other savory herbs. How long had it been since she sat at her own hearth, stirring her gram’s iron pot filled with lamb shanks and winter vegetables? She drew in a long breath, letting the aroma fill her mind with sweet memories as the crisp breeze tickled her ears and played with her hair. Even from where she stood, she could hear the children’s happy banter, carefree laughter. What did they know of war? She hoped they would never have to face what she had. If only she could promise them they would stay safe. If only . . .

She and her remaining companions had been treated well and shown honor in Haknoor, but they were strangers and didn’t fit into the routine of the closed community. Rhianna also realized that they were a burden to feed, for the resources of Haknoor were already stretched by the arrival of refugees. In any case, like her, most of her companions were eager to return to their own homes, and to whatever family they still had. Even Grubb, who would not walk again for many weeks or months, was as eager as any to depart, though he did not speak much. “I feel trapped,” he had confided to Rhianna. “I do not want to be a burden on the journey, yet neither do I want to be a cause for delay.”

She turned from the east and stepped carefully through the jumble of rock to join her friends. As they loaded and double-checked their packs, they once again discussed their plans for travel. Three of their group were traveling north, returning to their own homes and villages. They had the shortest distances to go. The best route home for Rhianna and the other three veered more eastward along the trade road.

“We should float home on the Tule River,” Valdon had suggested, when he learned that it passed through the hills less than a day’s journey away. Though his knee had recovered somewhat from the battle, he was still moving about with a limp and said he did not feel fit for hard travel. “Save us all the walking through this blasted wilderness. The river would bring us almost to our doorstep.”

Rhianna laughed, thinking Valdon was joking. When she realized the warrior had been serious, she said, “That way cannot be traversed. The Tule Falls is but one of a dozen waterfalls in the canyon that would crush you, and even if we could build boats, there would be no way to portage them around the falls.”

She pictured the thundering water, the roar that would fill her ears as she walked the river trail to and from her village to the distant lands. She loved the way the spray settled like mist on her arms, webbed her hair in water pearls, dispelled the heat of summer sun from her skin. How simple those pleasures were. How she had taken them for granted—the slow, peaceful days. She doubted they would ever return, with no end to this war in sight.

“We will just have to head north, on the trade road,” she told him with finality.

Valdon sulked but consented to the long walk home. After all, he was the one who had urged the others to choose her as leader, now that Alden was no longer among them.

Rhianna wished she could make it easier for him—for them all. Walking would take weeks.

With a sigh, she hefted her pack and started along the wide rutted road, the other six following her lead.

Although I didn’t add in all that much, those small bits of sound and smell and texture (water spray on her arms) make the setting more real to the reader. It doesn’t take pages of description to bring out setting through the POV character’s thoughts or feelings, but adds richness and interest to what might be a dry read, and it continues the ever-important task of connecting us deeply with that character.

If writers show setting—every setting, whether ordinary backdrop or essential locale—through the mind and heart of the POV character, they will avoid succumbing to this fatal flaw of fiction writing.

Your thoughts? Did you feel you got to know Rhianna better in the second example? What would you add or change?

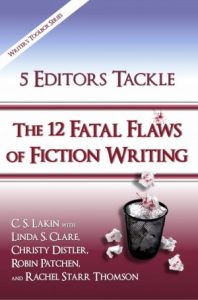

Don’t fall victim to the fatal flaws of fiction writing.

Don’t fall victim to the fatal flaws of fiction writing.

This extensive resource is like no other! With more than sixty before and after passages, we five editors show writers how to seek and destroy these flaws that can infest and ruin your writing.

Here are some of the 12 fatal flaws:

- Overwriting—the most egregious and common flaw in fiction writing.

- Nothin’ Happenin’—Too many stories take too long to get going. Learn what it means to start in medias res.

- Weak Construction—It sneaks in at the level of words and sentences, and rears up in up in the form of passive voice, ing verbs, and misplaced modifiers.

- Too Much Backstory—the bane of many manuscripts. Backstory has its place, but too often it serves as an info dump and bogs down pacing.

- POV Violations—Head hopping, characters knowing things they can’t know, and foreshadowing are just some of the many POV violations explored.

- Telling instead of Showing—Writers have heard this admonition, but there’s a lot to understanding how and when to show instead of tell.

- Lack of Pacing and Tension—Many factors affect pacing and tension: clunky passages, mundane dialogue, unimportant information, and so much more.

- Flawed Dialogue Construction—Writers need to learn to balance speech and narrative tags and avoid “on the nose” speech.

- “Underwriting”—just as fatal as overwriting. Too often scenes are lacking the necessary actions, descriptions, and details needed to bring them to life.

- Description Deficiencies and Excesses—Learning how to balance description is challenging, and writers need to choose wisely just what to describe and in what way.

Don’t be left in the dark. Learn what causes these flaws and apply the fixes in your own stories.

No one need suffer novel failure. You don’t have to be brilliant or talented to write strong fiction. You just need to be forewarned and forearmed to be able to tackle these culprits. And this book will give you all the weapons and knowledge you need.

“This book should be on every writer’s bookshelf.” —Cheryl Kaye Tardif, international best-selling author

Excellent post. So many young writers seem to be afraid of description, as if it would somehow slow the pace of the scene. What’s unrecognized is that visceral description adds layers to a scene, and it is conflict that keeps tension and therefore the pace intact. Without the description, however, the reader doesn’t experience the fictional world, and often emotion is therefore lacking.

I agree with Shannon Donnelly. Yes, I did get to know Rhianna better and also was able to picture the scene in a way that left me almost bereft of a picture in the first account. I am the kind of person who, when reading a good story, gets right into it and almost becomes part of the story. When I was part of a writers’ group a few years ago, the members always told me that my description was really good. That is one part of writing I love doing. Only when a particular place is of central importance to the character do I have them going to the same place at different times in the story. I hope my readers can get a feel for the settings as my characters react emotionally and physically to them. Great post, Susanne.

Another very useful post, thanks.

I think there is a very useful principle here, “The part shall stand for the whole”.

For me the trick is to slip in just a few details that point to the sort of location the characters are occupying. I learned this from the first crit I had of the scene in “Run from the Stars” where Jane is living in one cabin in a very big spaceship, and makes coffee for a visitor. Initially I’d just jumped straight into the dialogue without giving any sense of the size of the space or how it was furnished. Once I mentioned that Jane offered the visitor the best of the three chairs, got the filter coffee machine out of a locker and filled with water in the ensuite bathroom, and there was a curved wall, the space came alive.

This is the WIP (Luke is a rookie cop who lives with his widowed mother):

The scent of grilled bacon filled the little kitchen as Nancy put eggs onto her son’s plate. ‘Luke, there’s something I need to ask you.’

Luke refilled his coffee cup from jug on the breakfast table. ‘Yes, Mum.’

She turned with her back to the one big window. ‘Luke, I know you don’t talk to me about your cases…’

‘I’m not allowed to, that’s the rules.’

‘But please, you’re not in any trouble are you?’

He looked blankly at her. ‘No more than usual, why?’

‘You came home very late last night.’

‘I can’t tell you the details, but I am working a murder case. It’s my first one.’

‘Murder! Is it safe?’

Luke looked past her at the leaf-heavy oaks glowing in the early light. ‘Mum, murder means someone is dead. Being dead is never safe.’

Great information here. Thanks for the tips. Passive voice and the “ing” verbs sneak into my prose. I so need to learn more about this.

An excellent and helpful post. Thank you.