Utilize the Power of Breath Units to Write Masterfully

You may not have heard of breath units. In fact, if you Google this term, you’ll be hard-pressed to find any information on it.

Breath units are simply the number of words spoken in one breath.

Why should you care?

Because your writing style is all about breath units.

Your genre determines the kinds of breath units a writer should use.

You’ll notice this blog post, so far, is very similar to many blog posts you’ve read before.

These breath units are short.

For the most part.

And that’s because blog posts tend to share small bits of useful (one hopes) information.

And that’s why you’ll often see bullet points.

Small bites—small breath units—are stickier than long sentences.

When you read prose or poetry that isn’t written in paragraph form, breath units are often created deliberately by breaking up lines or laying out words in some creative fashion.

But everything written is laid out in breath units.

Short sentences, therefore, are going to be read slower, and longer sentences faster.

For example, using one full equal-length breath for each sentence, read this aloud (Vanessa Redgrave, speaking about audiences who came to see her perform):

We all come to the theater with baggage. The baggage of our daily lives, the baggage of our problems, the baggage of our tragedies, the baggage of being tired. It doesn’t matter what age you are, but if our hearts get opened and released—well, that’s what theater can do.

Which is the sentence that “sticks” the most? Which sentence feels most strongly stated?

It’s the first one—because it’s a short breath unit. Fewer words to digest and process in the same amount of time as the longer lines.

This isn’t to say you always exactly read every sentence (or phrase within a sentence separated by punctuation) in the exact same amount of time. This is a generalization. But it makes sense.

See what happens when I put the above passage into a different form:

We all come to the theater with baggage.

The baggage of our daily lives,

The baggage of our problems,

The baggage of our tragedies,

The baggage of being tired.

It doesn’t matter what age you are, but if our hearts get opened and released

—well,

That’s what theater can do.

Has anything changed for you? Now, other phrases stand out and demand your attention. Upon rereading multiple times, you might find new nuances to what you read because of the breath units.

Surely, our readers don’t often read our books out loud, but they do read our sentences in their heads in some fashion. While not actually using audible breath units, they do so mentally.

How?

The Importance of Beats or Pauses

I shared in last week’s post about writing style and how, when a line or phrase is pulled out and put on a separate line, it makes the reader pause. What it’s really doing is creating breath space.

When you come to the end of a sentence, you pause for a tiny moment. When you come to the end of a paragraph, you pause a little bit longer.

The end of a scene is a bigger pause, the end of a chapter even bigger, and the end of a section in a book the biggest pause.

To get our readers to respond and process what they just read and, possibly, what they are feeling.

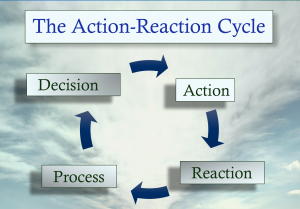

If you’ve read my posts or watched my module on Action-Reaction in my Emotional Mastery online video class (you can watch it for free by clicking on Preview), you’re very familiar with beats or pauses and the fact that all our characters, just like people, need time to react to, well, everything that goes on in a scene.

You can help drive home the character’s reaction by controlling the breath units of your phrasing.

Punctuation might be made of very small marks, but those marks create and break up breath units. Breaking up a long sentence into two or putting in an em dash or comma will add that second of pause.

For example, read this passage of a scene:

Diane ran to the corner out of breath and trying to flag down the bus. But the moment she arrived at the bus stop, the bus trundled off with a loud rumble and left her breathing exhaust. I had to get on that bus! Diane fretted. Now I won’t make that audition. My life is done.

Now read this revision:

Diane ran to the corner, out of breath. Trying to flag down the bus.

But the moment she arrived at the bus stop, the bus trundled off with a loud rumble. And left her breathing exhaust.

I had to get on that bus!

Diane fretted. Now I won’t make that audition.

My life is done.

Read them both aloud again, back to back. Notice how those different breath units create new emphasis. Not just the sentences broken up and put on separate lines but the punctuation create minor shifts.

Tiny shifts, tiny changes, can make a profound, massive difference.

You’ve heard me say every word matters—but also every piece of punctuation matters too.

You wield an amazing power. You can create and shape language. I don’t know if that blows your mind, but it blows mine.

Next time you pick up a best seller in your genre, study the breath units. Read the scene out loud. Pay attention to extra-long sentences that work and don’t. Note the sentences and phrases that are pulled out and set apart for emphasis.

That make you pause.

And reflect.

This is important homework if you want to nail your genre.

I love this concept of breath units. Now for a long pause. Reflect. Then reread parts of my WIP to see how I can improve. Thank you.

The problem with this is that creating new paragraphs for the sole purpose of structural impact (breath units) will make for an exceptionally high page count.

Well, it depends on what genre you’re writing in, and that’s everything. If you’re writing suspense, you need those isolated short phrases or words from time to time. Page count is actually rather unimportant because everything is measured by word count, which doesn’t change.

Perfect timing! I’m reading Erin Morgenstern’s The Starless Sea, and I’ve noticed how she uses short “breath units” (though I haven’t known the term) more than she did in The Night Circus. It’s like poetry; it puts the focus on certain passages, creating a rhythm that suits the scene.

The most memorable, powerful line in The Night Circus for me is “She does not see the train.” One short line at the chapter’s end. Nothing more is needed to not only remove a character from the story, someone’s dear sister, but to also explain so much and foreshadow what’s to come. So much horror in it, too, without describing anything. What more can be said?

Thanks for defining and explaining this!