Starting Your Scenes with a Bang!

Openings are a science unto themselves, be they openings for an entire book, for a chapter, or for a scene. One principle, however, is generally agreed upon: it is best to open with something happening. So let’s look at what’s involved with starting your scenes with a bang!

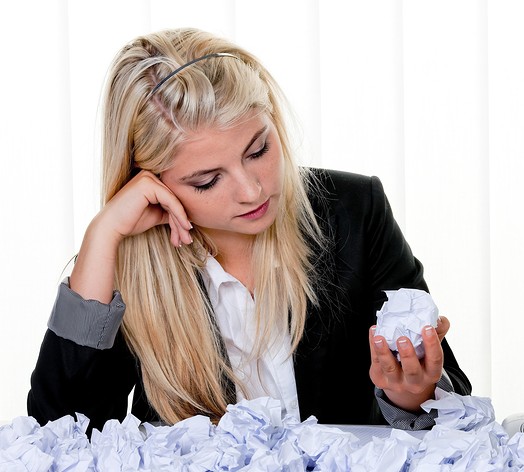

It’s true: too often we start reading (or writing) and nothing is happening.

Long explanations. Chapters of backstory. Characters sitting and thinking—about the past, the present, the future. Actions that lead nowhere. Weather.

Oh, the weather.

And then, finally, we write our way up to where the story really takes off—several paragraphs or even whole chapters after we begin.

The problem here is that while we are getting warmed up, readers are trying to enter the story world—and if they can’t get in soon enough, if the opening bores them or feels irrelevant or rambling, they are liable to move on before we do. All the way to a different book.

When we consider the immensity of history, information, and world creation most writers are trying to fit into two hundred or more pages, it’s not surprising we need to work up to our stories. But readers won’t toil through pages of preparation, information, or meditation before the story really begins. They need to engage, to get immersed in the action and become intimate with the characters quickly. Some say within the first page.

So when you edit, it’s time to take a hard look at your opening. Begin in media res—get to the good part. Engage readers right away through dialogue and relevant action, all of it building up the scene’s purpose. Raise questions. Use characters and emotion to invest actions with meaning. Stir up tension. Intrigue. Mystery. Excitement.

Find where your story begins, and do as the king in Wonderland once told Alice: begin there.

And keep in mind: thinking does not qualify as something happening. Not only that, but many times this type of “sittin’ and thinkin’” scene is so loaded with backstory that readers don’t know when the real story begins—or worse, they don’t care.

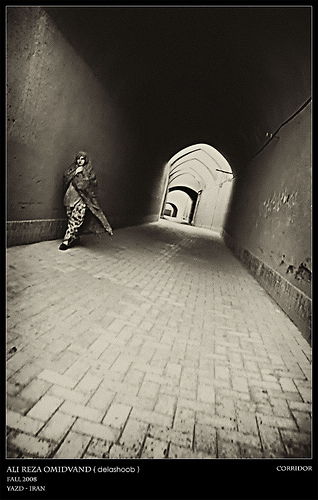

In Medias Res: Cutting to the Chase

In medias res. If you’ve been writing for some time now, chances are you’ve heard at least one seasoned writer or editor tout its importance. Or maybe not.

Latin for “in the midst of things,” in medias res refers to the literary technique of starting the story in the middle of the action instead of using descriptive narrative to provide background and build up to the action. It’s the principle we’ve been discussing in this section, and it matters so much because we only get one chance to make a first impression. If our story doesn’t capture readers’ attention in the initial few pages (some say in the very first page), many readers simply won’t read on. Even if the story’s pace and action pick up soon after, it won’t matter, because we’ve already lost our reader.

So what grabs a reader’s attention? Dialogue and action, to name two. Yes, description is also important—it embellishes with setting and often-needed background. But in most cases, description can be interspersed throughout the story. Dialogue breaks up the narrative and provides pertinent information without dumping it on the reader all at once. And by starting in the middle of the action, questions are posed and tension is built, making the reader ask questions. Readers want those questions answered, so they continue reading.

Intersperse description to ground the story’s setting and situation, and continue to do that as the story plays out. But above all, engage the reader early on. We have the rest of the story to add embellishment.

Think of in medias res as getting to the good part. As fiction writers, we can grab our readers’ attention right away by opening with action and dialogue that will build tension and get readers asking questions and wondering what will happen next.

The Wilson Principle

To hook your readers and get the story going quickly, your POV character needs someone to interact with. If you write only her thoughts, she has no one who will disagree with her. There is no variety or stimulating action. While it can sometimes work, writers risk losing readers’ interest by taking such an approach.

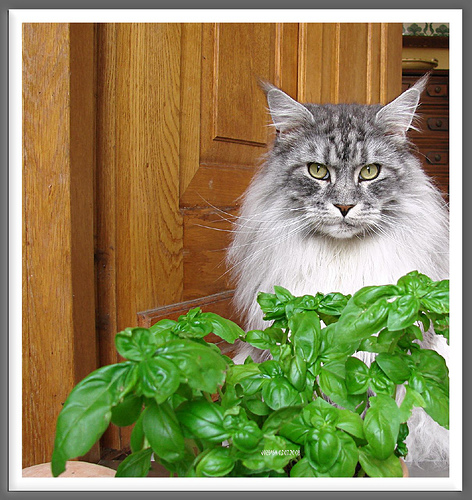

In the movie Cast Away, Tom Hanks finds himself marooned on a desert island. He has no one to talk to, no one to interact with. That’s why he invents Wilson, the volleyball. He draws a face on the ball and gives him some seaweed hair. Voilà! Tom Hanks’s character has a sidekick.

In the film, Wilson becomes someone for Hanks to confide in and get angry at. Wilson sets off a range of emotions in Hanks. In your novel, getting at least one more character on stage with your POV character gives this same advantage. Readers are enlivened through the possibilities of dialogue, body language, and physical action. You can sprinkle a touch of backstory here, but when your character is not alone, you no longer must rely so heavily on character memories, which, especially in your chapter 1, have little significance to readers.

When you write a scene, note the number of other characters on stage. People are the usual choice to join your character, but pets or even a personified volleyball can provide a way to include dialogue and action in the scene. Use the Wilson Principle to keep your audience engaged.

In Conclusion . . .

Take some time to look at your novel (or short story) opening, as well as your scene openings. Consider how and where you are showcasing your POV character. Is she doing boring, passive things? Thinking a lot without being shown in action? Are you intruding as the author to foreshadow things that will occur later, things your character can’t know?

We’re tempted to explain in detail our backstory, character motivation and reasoning, and what our setting and characters look like. But no one wants a truckload of information dumped at the start of a story. Readers want to be swept away, transported—not buried under a ton of rock.

Starting your scenes with a bang every time is a surefire method to keep readers engaged and turning pages. Of course there is much more to writing great scenes … and you can learn it ALL in my online video course 8 Weeks to Writing the Commercially Successful Novel.

Jam-packed with probably a year’s worth of instruction, dive in and go at your own pace, studying the dozens of sample scenes and doing the homework. I can assure you if you learn and apply the technique, your writing will be supercharged! Hundreds of writers have learned this content in my master classes and put the skills to use in small critique groups. It works!